by Boni Cairncross and Louise Curham

Boni Cairncross is an artist interested in temporality and archives.

Louise Curham is an artist, archivist and filmmaker, and a researcher at University of Canberra’s Centre for Creative and Cultural Research.

The exhibition Making Art Public has been created from archives, remakes and documentation of past Kaldor Public Art Projects and is itself Project Number 35: Michael Landy. Unlike most exhibitions, in this show the residue of earlier temporary public art is used to create a new kind of artwork, one that describes the original work but is not itself that original work (even though it may contain fragments). In this article, Boni Cairncross and Louise Curham reflect on their experience of the exhibition, and their attempt to create an archive of intangible experiences in the form of instructions that allow momentary experiences to be recreated and shared.

We (Boni and Louise) decided to make an “experimental archive” of Making Art Public in order to respond to their questions about archives, evidence, sets of criteria and reimaginings of archival material. Making Art Public is both a major survey exhibition of the 34 projects staged by Kaldor Public Arts to date, and the 35th project in which artist Michael Landy worked with the archival material to present this overview.

We discussed ways to make a “mini-archives” that was the opposite to what people usually think of as archives. For us the commonsense meaning of archives is a set of evidence linked to events from the past. The archive is a trace of things that have been done. We soon decided to replace the word experimental with “experiential”. We agreed we wanted to keep working with evidence, but we wanted to look for evidence that wasn’t so obvious.

Like many of the projects represented in the boxes, this exhibition is temporary. Technically it could be restaged at some point in the future. The boxes could be in the same configuration, the way we walk around them might be not so different, what’s in them would be similar. But what about our embodied experience of the elements that make up the exhibition?. In other words, even if your common sense perception is that you’re the same person, and the things you’re looking at are the same, in reality we’re never the same again. All the time. With this in mind we decided to focus on our experience of viewing Making Art Public, right now, today, on Tuesday November 12, 2019..

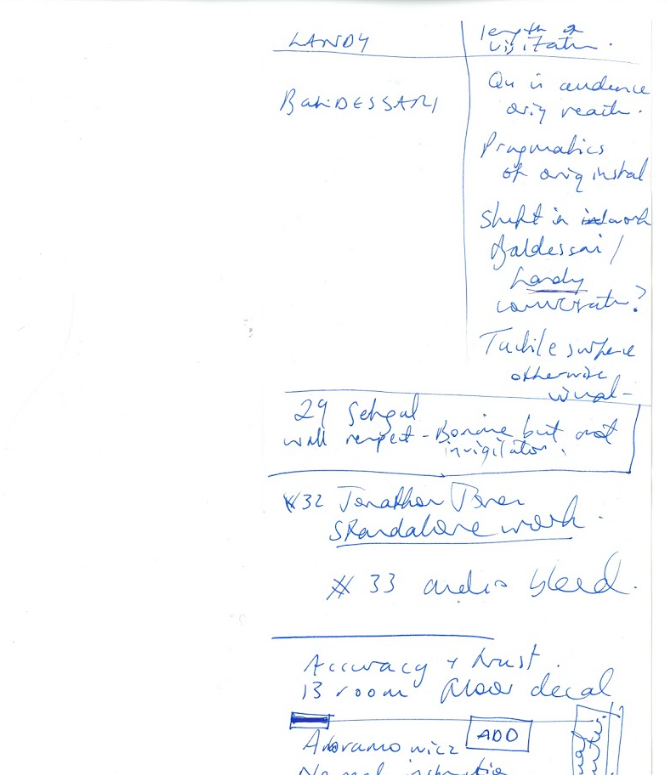

To make an archive, you need to do something. As a rule of thumb, archivists hold that about 5% of the residue of an event or experience is worth keeping – and would meet the criteria of “significance”. That evidence gets drawn together to form the archives. The evidence from the walk that Boni and Louise went on include two audio recordings, a handful of photographs and our notes. We were “engineering” an archive and we had our selection criteria. Many art experiences use your eyes a lot but ask less of your ears, touch or taste. So our selection criteria for our archives is based on the moments in the exhibition where our attention was called by sensing organs other than our eyes, where our ears and our sense of touch were able to do some work. We were thinking about things that tend to get left out or overlooked in records of art experience – the “extra visual”.

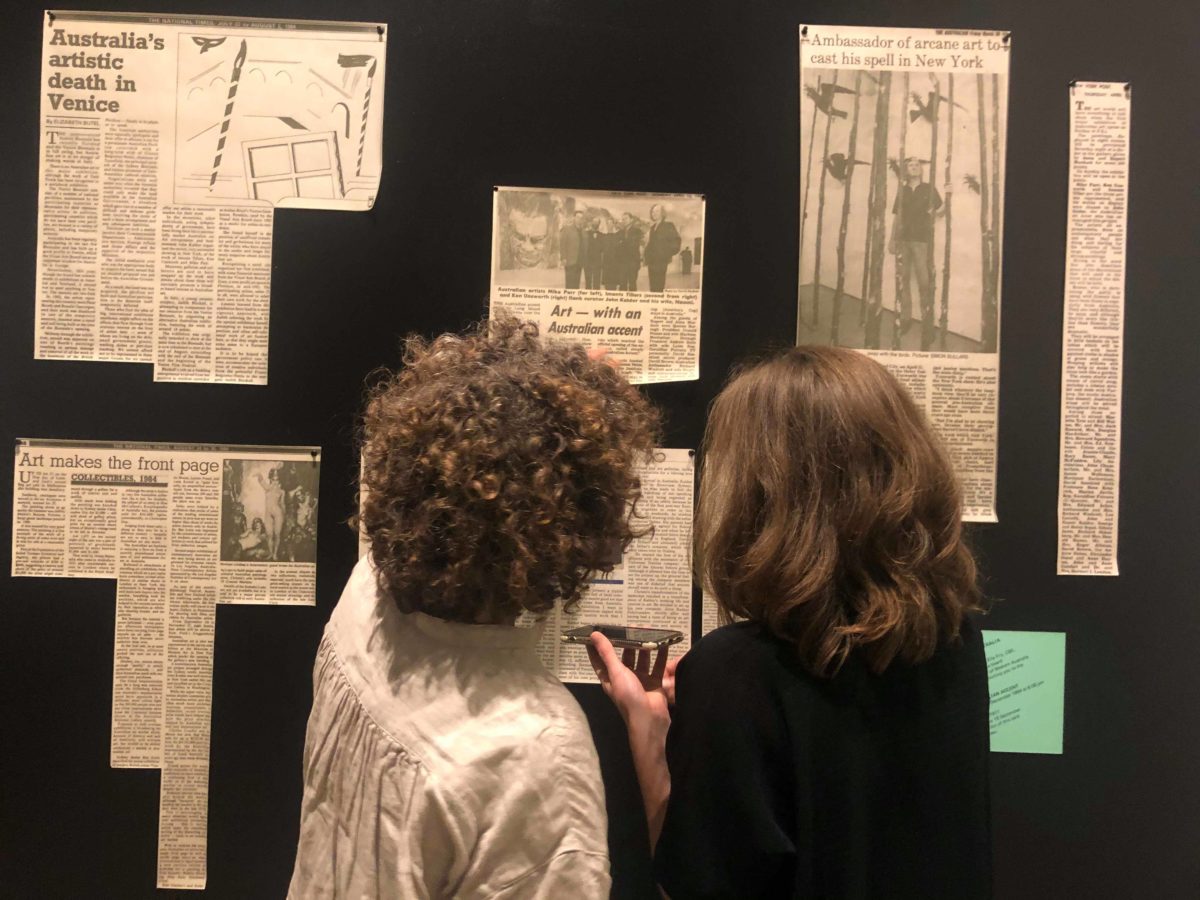

What did we actually do? We walked around Making Art Public (Kaldor Public Art Project 35: Michael Landy), alert to what was extra to the visual material that Michael drew together. By “extra to the visual”, we mean what we heard, touched and imagined. We were looking at the exhibition, but also at how the public were interacting with the projects and with each other.

Our “archives” don’t actually exist at this stage. We’ve got the audio recordings, the notes and the photographs, but we haven’t physically winnowed them down to the 5% we think constitute the significant evidence that should make it into the archive. Instead we have made a “finding aid” about that 5%, in the form of instructions that guide you through a sense of our experience of Making Art Public.

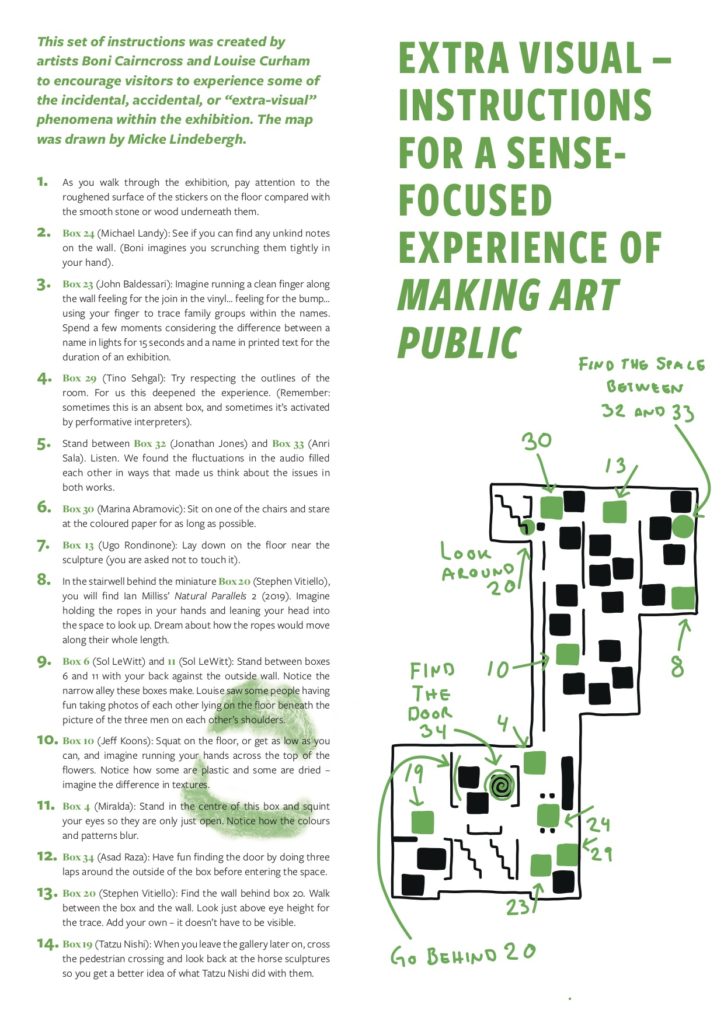

We invite you to access our “archives” and share our experience by following these instructions, which are printed here alongside a handy lift-out map of the exhibition drawn by Micke Lindebergh.

Archival documentation written by Louise on her experiential voyage through the exhibition

1. As you walk through the exhibition, pay attention to the roughened surface of the stickers on the floor compared with the smooth stone or wood underneath them.

2. Box 24 (Michael Landy): See if you can find any unkind notes on the wall. (Boni imagines you scrunching them tightly in your hand).

3. Box 23 (John Baldessari): Imagine running a clean finger along the wall feeling for the join in the vinyl … feeling for the bump … using your finger to trace family groups within the names. Spend a few moments considering the difference between a name in lights for 15 seconds and a name in printed text for the duration of an exhibition.

4. Box 29 (Tino Sehgal): Try respecting the outlines of the room. For us this deepened the experience. (Remember: sometimes this is an absent box, and sometimes it’s activated by performative interpreters).

5. Stand between Box 32 (Jonathan Jones) and Box 33 (Anri Sala). Listen. We found the fluctuations in the audio filled each other in ways that made us think about the issues in both works.

6. Box 30 (Marina Abramovic): Sit on one of the chairs and stare at the coloured paper for as long as possible.

7. Box 13 (Ugo Rondinone): Lay down on the floor near the sculpture (you are asked not to touch it).

8. In the stairwell behind the miniature Box 20 (Stephen Vitiello), you will find Ian Milliss’ Natural Parallels 2 (2019). Imagine holding the ropes in your hands and leaning your head into the space to look up. Dream about how the ropes would move along their whole length.

9. Box 6 (Sol LeWitt) and 11 (Sol LeWitt): Stand between boxes 6 and 11 with your back against the outside wall. Notice the narrow alley these boxes make. Louise saw some people having fun taking photos of each other lying on the floor beneath the picture of the three men on each other’s shoulders.

10. Box 10 (Jeff Koons): Squat on the floor, or get as low as you can, and imagine running your hands across the top of the flowers. Notice how some are plastic and some are dried – imagine the difference in textures.

11. Box 4 (Miralda): Stand in the centre of this box and squint your eyes so they are only just open. Notice how the colours and patterns blur.

12. Box 34 (Asad Raza): Have fun finding the door by doing three laps around the outside of the box before entering the space.

13. Box 20 (Stephen Vitiello): Find the wall behind box 20. Walk between the box and the wall. Look just above eye height for the trace. Add your own – it doesn’t have to be visible.

14. Box 19 (Tatzu Nishi): When you leave the gallery later on, cross the pedestrian crossing and look back at the horse sculptures so you get a better idea of what Tatzu Nishi did with them.

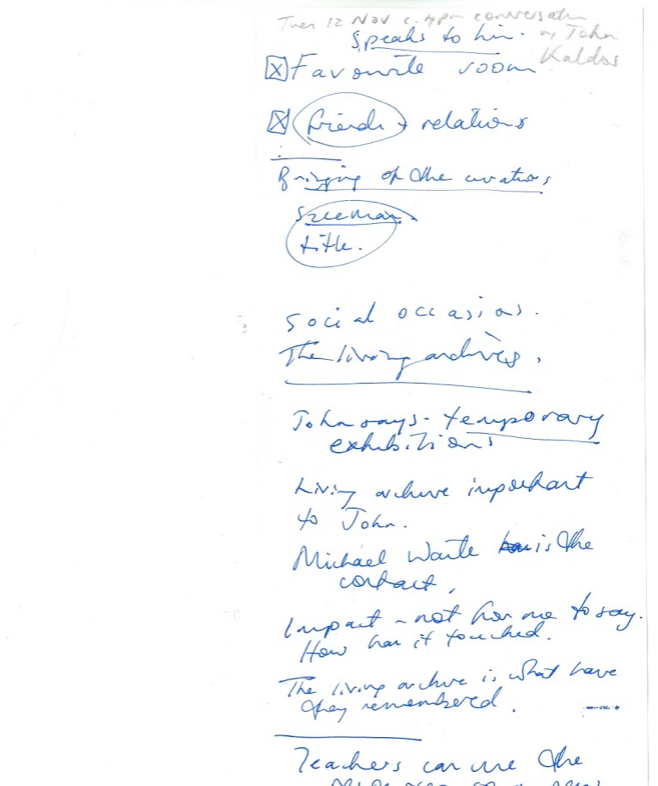

At the end of our efforts to record the extra-visual experiences of Making Art Public (Kaldor Public Art Project 35: Michael Landy), we ran into John Kaldor himself. He kindly had a short chat with us. We commented that it must be like meeting a handful of old friends, seeing this exhibition, and we wondered if there was a project that speaks particularly loudly to him – to which he replied that they are all so different. We were curious if he keeps in contact with the artists. John explained that it varies but he noted that he does regularly catch up with some, Richard Long and Gilbert & George, for example.

Our conversation moved to the impact these projects have had on Australian artists and audiences. It seemed to us that the early Kaldor Public Art Projects, such as Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Wrapped coast – one million square feet, Little Bay, Sydney, Australia (1969), was a significant experience for Sydney artists. John said that it was not for him to comment on the impact, and he spoke enthusiastically about The Living Archives. He emphasised that this was particularly important as the projects were all temporary exhibitions. (Editor’s note: The Living Archives project involves collecting stories from people who experienced specific projects over the last 50 years – you can find them on the Kaldor Public Art Projects website)

With Kaldor’s focus on temporary projects in public spaces, the archive becomes increasingly significant. It is the trace, the things that remain behind. What we have attempted to do is think about the archive both practically and metaphorically. How an archive is both the 5% record of things that have been done, and a space for imagination, reinterpretation and play. In thinking metaphorically about the archive, we wondered about the gaps that inevitably exist. For now, we experimented with ways to capture the “extra visual” stuff and a sense of an experience of Making Art Public. Yet this list can continue to evolve. On this note, we ask that you please contribute some of your own evidence by recording your discoveries of “extra visual” stuff in a letter to the Extra! Extra! editor.