by Chris Nash

Chris Nash was Professor of Journalism at Monash University, and previously Director of the Australian Centre for Independent Journalism at UTS.

Over the five weeks of EXTRA!EXTRA! Chris Nash has published a developing analysis of Hans Haacke’s art as a form of investigative journalism. Nash’s final article ended with a discussion of “replicability”. He writes:

“Like any scientific experiment or observation, Haacke’s art is replicable by other artists in the same way that scientific research has to be replicable and verified to be validated. The same validation requirement applies to journalism, which is why Haacke could use journalistic methods in his research”.

In this bonus “stop the press!” article, published simultaneously in EXTRA!EXTRA! and The Saturday Paper, Nash puts this principle into practice. In the spirit of Hans Haacke, this dual publication means the article can be categorised as art here and journalism there. Either way it replicates Haacke’s approach to investigating the mechanics of the real estate market.

Real estate manipulation was at the centre of the controversy that blew up around Haacke in the early 1970s, and what is more representative of Sydney’s actual living culture than its obsession with real estate prices? Journalism in Australia has been propped up by this obsession. Real estate was a major part of the old classified advertising phenomenon, the fabled “rivers of gold” that funded Australian newspaper journalism until the internet era. Of course, online real estate advertising still generates vast amounts of cash for the mainstream media but very little of this revenue flows towards investigative journalists.

But the media also functions ideologically, to actively promote markets and to ensure the profitable real estate obsession continues. In this article Chris Nash takes his research on Haacke one step further, and like Haacke, he investigates some seriously questionable media practices in real estate advertising.

Ian Milliss

My parents married, bought a double block of land in Merrylands in the late 1940s with a War Service Loan, and started a family. Merrylands was then on the western fringe of Sydney suburbia, these days it’s near the geographic centre. There was an old weatherboard house on one block where we lived until the late 1950s while they built a new fibro house on the vacant block and sold the old place. They owned and lived in that house till they sold it to move into a retirement village in December 2003, getting the excellent price of $596,000 at the very tail end of the 1996-2003 property boom.

The house was bought by a bloke who said he wanted to use it as a childcare centre, but that was never going to happen because of asbestos in the fibro cladding, and it was rented out. He sold it three years later in December 2006 for $420,000. That price delivered a nominal loss of 30%, but if you factor in the interest payments on the mortgage offset by the rent received, transaction costs on the sales, inflation, and forgone interest if he’d had his money on term deposit for three years, the loss in real terms was probably well above 40%.

Domain.com.au offers what it calls a “full property history” facility on its website, which provides information about previous sales for properties “provided under licence from the Department of Finance and Services, Land and Property Information”. The information is compiled and provided by Australian Property Monitors (APM), part of the Domain Group established by Fairfax Media and now 60% owned by Nine.

The history provided for my parents’ home includes the following three sales over the period 2000 –2010:

2000 ($300,000);

2006 ($420,000); and 2010 ($425,000).

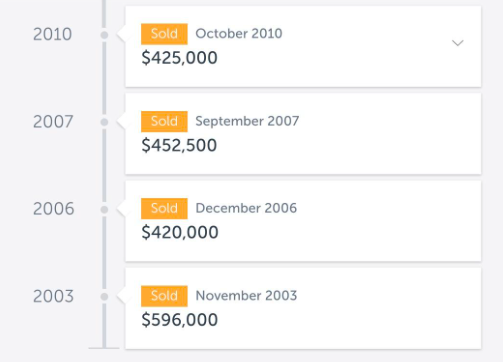

The sale price history for the same property on realestate.com.au is different: 2003 ($596,000);

2006 ($420,000);

2007 ($452,000); and 2010 ($425,000).

Realestate.com.au includes four sales over the period – two of them apparently loss-making – while Domain has only three sales and omits the loss-makers.

There was no sale in 2000. My parents owned the home till 2003 and used the money from the sale to buy into the retirement home. I have the sale documents. The 2000 sale in the Domain history is a fabrication. What’s more, the omission of the 2003 sale for $596,000 hides the fact that the property lost 30% of its nominal value over the following three years. Taken with the false sales report it implies a profit of 40% – $120,000 on $300,000 over six years – instead of a loss of 30% – $175,000 on $595,000 over three years.

The Domain history omits another sale (in 2007) which incurred a second apparent loss (of $27,500) when it was sold in 2010, although by that time the large quarter-acre block had been subdivided, with a second house to be built subsequently on the separated back of the original property. Taken together, Domain’s omission of two apparently loss-making sales, and the fabrication of another sale, implies that no loss was ever made on any sale of that property. It is deceptive.

Domain.com.au reported 586 auction results for the weekend of 30 November, 2019. A 10% representative selection was made by taking the first sixty properties (with specified sale price) listed alphabetically by suburb and street (the relationship between property type and suburb/street name is random). Domain reported only five properties where historical losses have been indicated. Two of them were adjoining lots on a busy road in Bankstown that a quick succession of owners seem to have tried to assemble for joint sale to an apartment block developer. (Realestate.com.au also failed to report a loss on one of those two properties, but not the other.) The other three properties were all in Bexley, and subject to rapid-fire turnover by speculators. All of the other 55 properties in the Domain random sample, drawn from across greater Sydney and including both houses and apartments, show nominal profits only on any sale.

However, in four of the sample properties Domain omits a loss-making sale that realestate.com.au reports. An apartment in Arncliffe was sold for $365,000 in 2013 at a loss from the 2008 purchase price of $385,000, and an apartment in Balmain East went for $420,000 in 2007 at a loss from the purchase four years earlier for $447,500, but those sales are not reported in Domain. Nor was a loss of 47% on a Belfield property between 1998 and 1999 (from $245,000 down to $130,000), or a quick loss of $5,000 (1.6% of the price back in the day) over two months on a Baulkham Hills house in 1993.

Of nine properties sold on 30 November 2019 where there were current or historic losses, Domain reported losses in only five, and they were for speculators making fast turnovers. For the other four properties the loss-making sales were omitted. There are some absences in the realestate.com.au histories of the total sample of properties, but only one historical loss omitted, as part of the Bankstown speculation: all other losses are included.

This improbable pattern in the Domain sample spans the bursting of the 1996-2003 boom, the following stagnation till well after the Global Financial Crisis, and the sharp deterioration since the most recent peak in late 2017. The clear implication is that individual buyers of real estate very rarely lose money on their purchase, whatever and wherever they buy, even though the general real estate market might decline.

How could that be? It is true that property owners try to avoid selling into a falling market, but in a downturn or prolonged stagnation some sellers don’t have much choice. No doubt the ‘price withheld’ tag on some reported sales could be a fig leaf for an embarrassing loss. But following the falls from the 2003 and 2017 peaks, how come only ‘speculators’ delight’ properties lost value in a random representative sample, and everybody else is supposed to have made a nominal profit despite two housing price busts and ensuing stagnations? And how could the loss-making sales on five properties out of 60 (8.3% of the total) be omitted by accident, and one false report of a profit-producing sale be fabricated?

A spokesperson for Domain said “Domain Group Policy is not to alter or remove past sales data supplied by the state and territory governments. The data is automatically sent to Domain (via APM) and updated regularly by the state government department. If we have a report that there is a major problem with the sales data, then our internal support team have an option to hide the entire history for the property. They have no capability to pick and choose which transactions to hide, all or nothing.”

Domain made no response to specific questions about the discrepancies evidenced above and the apparent divergence from their stated policy.

Professor Bill Randolph, Director of the City Futures Research Centre at UNSW, expressed surprise at this reported situation because it would be “a bad business move” risking discovery and brand damage. However, he said that the “buying and selling of real estate is much more managed than most people realise, and is highly nuanced with different sectors playing support roles for the main game of generating sales. Press coverage of the real estate market is very much a good news story.”

The general pattern of optimistic reporting on the real estate market is far from unique to Domain. For my own PhD research I did a detailed analysis of journalism about the Sydney residential real estate market in the 1996-2003 housing boom. Real estate advertising historically has been one of the three main sources of the ‘rivers of gold’ that funded the newspaper industry, and Domain is still fundamental to the economic fortunes of Nine media.

The housing boom beginning in 1996 saw the take-off of a massive increase in household debt to over 150% of household disposable income, and a catastrophic doubling from 6 to 12% of interest payments as a proportion of household disposable income. Meanwhile, household savings went negative and outstanding balances on credit cards tripled to 7% of household disposable income. By the end of the boom in 2003, mortgage debt had surpassed both business and personal debt as a proportion of GDP, while government debt was negligible. Over the same period, Sydney house prices doubled.

But after the end of the boom, house prices in western and south-western Sydney dropped more quickly than in the rest of the country. Hence the 30% drop in my parents’ home over 2003-2006. With the GFC in 2008, the falls spread to the inner-city, eastern and northern suburbs, and didn’t recover for years.

But to read the real estate journalism at the time (in The Sydney Morning Herald and The Daily Telegraph in my study), it was always a good time to enter the market, as either a seller or buyer, no matter what stage the cycle was at. Housing affordability, household debt and increasing homelessness were side issues dealt with elsewhere in the news, and largely a welfare issue. They had little to do with the market. The overarching imperative for real estate reporting is to keep the market optimistic and buoyant, regardless of the economic and social costs beyond.

The long and the short of it is that very little of what journalists say about real estate should be taken at face value. Their very jobs depend on keeping the market busy and expansive. Misleading sales histories are just a straw in the wind blowing through the domain of endless joy. Buyer, and seller, beware.

Chris Nash was Professor of Journalism at Monash University 2008-17, and a Walkley Award-winning journalist at the ABC.

chris@chrisnash.com.au